The daughter of the man tasked with selecting the Unknown Soldier, Brigadier General Wyatt, turned 100 this year and was reunited with her father’s medals by the Museum Director, Danielle Crozier.

At 100 years of age, Laetitia Hardie has lived through two world wars. She was born on 21 August, just a few months shy of the armistice on 11 November 1918. She is still able to remember her childhood near Whittington Barracks, where the North Staffordshire Regiment were based. She grew up there with her sister Patricia, mother Marion, and her “quiet and high principled” military father, Brigadier General Louis John Wyatt, DSO DL.

Brigadier Wyatt, born in 1874, was a professional military man, having joined the army soon after leaving Aldenham grammar school. He joined the North Staffordshire Regiment in 1895 and fought in the Boer war, being injured at Jackfontein in 1900. He disembarked in France in 1914 as a Major, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1916. By 1920 he had been promoted to the post of General Officer in command of British troops in France and Flanders, as well as Director of graves, registrations and enquiries.

It was in this capacity that, just after midnight on the 8th November 1920, in a makeshift chapel at St Pol in France, Wyatt chose the body of a soldier to represent the Unknown Warrior. This unidentified body, who could have come from any background, was chosen to represent all the soldiers, airmen and sailors who were lost in this war. He would be buried among kings in Westminster Abbey with a reverence he could never have imagined in life.

Hundreds of thousands of men had been killed during the war, gunned down in the fields or drowned in the trenches as they filled with water. When hostilities ended, their bodies were exhumed and reburied in nearby cemeteries, but many of them could never be identified. These were the men that the Unknown Warrior needed to represent – the men who would be forever missing, presumed dead. Countless widows and bereaved parents could visit the Unknown Warrior’s grave and feel some modicum of comfort.

Wyatt rarely spoke about the Unknown Warrior, but he did write a letter detailing exactly how he chose the body because he had concerns that the facts were not being reported accurately: rumours circulated. People whispered, for example, that the identity of the Unknown Warrior was known from the beginning. Wyatt wrote to the Telegraph on 11 November 1939, two months after the second world war had broken out, and on the 21st anniversary of the armistice.

He said: “The four bodies lay on stretchers, each covered by a union jack, in front of the altar was the shell of the coffin which had been sent from England to receive the remains. I selected one, and with the assistance of Colonel Gell, placed it in the shell; we screwed down the lid. The other bodies were removed and reburied in the military cemetery outside my headquarters at St Pol. I had no idea even of the area from which the body I selected had come; no one else can know it.”

Wyatt finishes with a description of the coffin being carried on the destroyer HMS Verdun to Dover and alludes to the encroaching horror of the second world war. He wrote: “Then HMS Verdun moved off … carrying that symbol which for so many years, and especially during the last few months, has meant so much to us all.”

When Mrs Hardie was aged around 20, just before the outbreak of the second world war, she went to the various war grave sites in northern France with her mother. “We visited the place where the selection of the Unknown Warrior had been made. We went up the rickety steps and I remember it was very plain inside, with a rough wooden floor. There were some trees around.” While her father didn’t discuss the Unknown Warrior, Mrs Hardie thinks she understands why. “My view is that he regarded it as a sacred trust that had been committed to him, and that some things are just too sacred to ever be discussed.”

During the second world war, Hardie joined the Red Cross as a voluntary aid detachment nurse and became an expert in anti-gas treatment. “Though my father rarely talked about the war,” she recalls, “I do remember him abhorring the use of gas because of the horrific injuries it caused, and this inspired me to do anti-gas training.”

She married Patrick John Hardie, who qualified as a doctor just before the second world war. He served with the British forces during the war, treating some of the emancipated prisoners when the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was liberated.

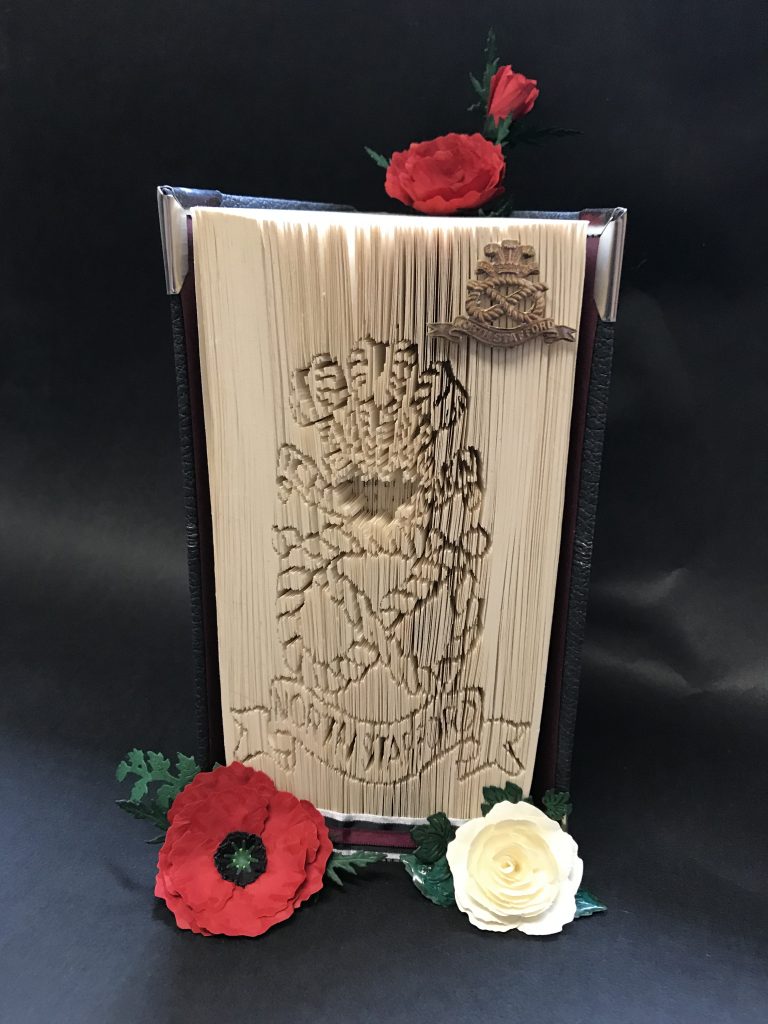

Earlier this year, Hardie made contact with the Staffordshire Regiment Museum to request photographs of her father’s medals. It was then that the Director, Danielle Crozier, began to look into Wyatt’s story and realised that he had left behind an extraordinary legacy by choosing the Unknown Warrior. Instead of sending a photograph on such a unique occassion she arranged to attend Mrs Hardie’s 100th Birthday party herself. She took with her Brig General Wyatts medals and a very special unqiue present for her from the Museum Trustees.

Leave a Reply